The Hop Days in Sauk County

By Hon. John M. True

Paper Read Before the Sauk County Historical Society

January 25, 1908

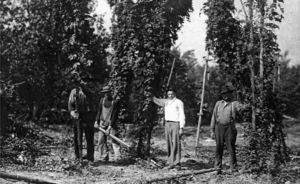

Hop Pickers

Sauk county will probably never again be so overwhelmed by visions of general wealth as it was in the hop excitement of the “sixties.”

The raising of wheat for the market, that had for years been the leading pursuit of the farmers of the county, on account of the deterioration of the soil and the ravages of the chintz bug, was becoming unprofitable. Live stock husbandry and dairying had not established a foot-hold, and farmers were in position to welcome a new departure in business, when the raising of hops—to be sold at very remunerative prices—seemed to come as a veritable “Godsend.”

Conditions of soil and climate were well adapted to the growing and curing of an excellent quality of hops, and soon Sauk county was among the leading counties of the West in acreage and production of the crop.

We find, from the statistical reports in the office of the Secretary of State, that in 1867 Sauk county raised approximately 2,000,000 pounds of hops, this being considerably more than one-fourth of the entire crop of the state.

Pioneers in the industry in a small way had demonstrated that hops could be raised at a profit for from ten to fifteen cents per pound, and when prices suddenly went up to twice that amount, and higher, there was a general rush into the business, until it is safe to say that in 1866 and 1867 more than sixty per cent of the farmers in the townships of Greenfield, Baraboo, Fairfield, Delton Dellona, Reedsburg, and Winfield had hop yards of very respectable dimensions, while other townships in the county were more or less extensively engaged in the work. Many who owned no land rented from two to ten acres, and started in to make a fortune.

Hop poles were in great demand, and timber lands were scoured for trees of proper size for making them; the value of such lands being reckoned upon the number of hop poles they would yield per acre. Poplar poles that would only last two or three years were extensively used, while oak poles brought as high as $15.00 to $18.00 per thousand. Tamarack, then found in large quantities upon the “Great Marsh” in Fairfield, made the most durable poles, lasting for a long time. I venture to say that some old tamarack hop poles are yet doing service as auxiliaries in fence building upon Fairfield farms.

The sale of hop roots became an important adjunct to the hop raiser’s revenue, as the roots of the older plants needed trimming in, or “grubbing” in the spring, and as seed roots were very much in demand, these sold for from $15.00 to $25.00 for root enough to set an acre.

The most expensive part of the hop grower’s outfit was the hop-house—affording room for storage and the drying kiln, the heat for which was furnished by huge cast iron heaters, denominated “hop stoves.”

Many of these buildings were quite elaborate, and some of them even pretentious in style and finish. These old hop-houses are yet doing service as granaries or stables, upon many Sauk county farms, though in most instances the ventilators that adorned their roofs have been removed, and the great stove and kiln are no longer a part of the inside fixtures.

At the time of gathering the crop, hop-pickers were in great demand. Young women were brought in by scores, from other parts of the state, while the local force of women and children from non-hop-growing families deserted home duties for the excitement and profit of work in the hop yard.

Hop-raisers’ homes were turned into boarding houses, and to attract and hold the much desired field help, elaborate bills of fare were furnished. To the merry, rolicksome routine of the day’s work in the field, was added the nightly dance or entertainment, one large grower vying with another in__________________________________________.

Pickers were paid by the box for hops cleanly picked from the vines, and prices for picking were fifty cents and sometimes more, per box. In picking, hops were not pressed down in the boxes, but allowed to rest lightly as thrown in. Each stand contained four boxes.

A man, termed “pole-puller”, was allowed for every two stands,--it being his duty to keep pickers supplied with vines upon the poles ready for picking, and later to strip the poles of the denuded vines and place them in large, round, upright stacks.

As boxes were filled, hops were emptied into sacks and carted to the hop-house for drying. After being cured they were pressed into large bales and covered with canvass, when the crop was ready for the market.

Competition in buying was usually sharp, and buyers drove through the county from farm to farm, bidding upon holdings of farmers, prices varying more or less according to the quality or extent of the product, but usually ranging from forty cents per pound upward.

When a man had “sold his hops” he was supposed to be in funds and ready to pay the bills that for months had been accumulating upon the expectation of the sale now made.

During the years of good crops and high prices he easily met these obligations, though they ran into large figures, and had money left for the purchase of additional conveniences or luxuries, though he seldom deemed it necessary to “lay by” any present surplus against future needs as he did not question the stability of his present source of wealth.

Few farmers were really enriched by the cultivation of hops, except as through the work, they had erected buildings for hop-houses, that, though not well calculated for the use to which they were later put, served as stables or granaries in later years, or in the possession of what had been considered luxuries when bought, that remained as reminders of the days when they were rich, or thought themselves so.

As we look back upon what was for a time termed the “hop-craze” we recall some amusing, as well as later pathetic incidents, growing out of the rapid accumulation of money by those who had been unaccustomed to wealth;—the certainty that there was to be no end to this influx of riches, and then the sudden and complete collapse of the whole industry, upon which they counted while contracting debts—that left them in greater financial straits than ever in the old days.

While high prices prevailed, to be the owner of a hop yard was a guaranty of consideration almost anywhere. Those of us who were not cultivators of the vine stood meekly by when we visited our merchant for needed supplies, while our hop-growing neighbor secured, upon credit, the choicest articles for sale.

Merchants did an extensive and lucrative business, for there was little “haggling” over prices if goods were considered desirable. Sharing the optimistic feelings of patrons, they encouraged them to make heavy purchases and run large bills. Higher priced goods were bought and placed on sale to meet the greater requirements of people who had been accustomed to necessary economy, but who now lavishly gratified their enlarged though sometimes, vulgar tastes.

Up to this time the almost universal means of conveyance among farmers, had been the farm lumber wagon in summer, and the same wagon-box upon the farm bob-sleds in winter. Now, light buggies and cutters were demanded, and sold quite extensively.

As with the newly rich of later times who have “struck oil,” discovered a mine, or been sharp and unscrupulous enough to work a successful graft upon the public,--nothing was then too good for our hop-growing farmers, and they indulged their fancies at will.

Disaster came almost as “a bolt from a clear sky.” In 1868 a large crop had been secured at an expense greater than ever before, and all hopes were centered in its sale, when, partially from over production, and partially from injury to the hops by insects, prices fell off very decidedly. Some sold their crops for what they could get, but many growers held their hops over hoping for better prices next year, when the bottom dropped completely out of the market.

The “hop-crash” brought widespread disaster. There was scarcely a person in a community who was not affected by it. Even the women who had picked the hops, in very many instances had not been paid for that service. Merchants, blacksmiths, carpenters, doctors, and even lawyers, had charges upon their books that they could not collect.

Little had been produced upon Sauk County farms, for sale, except hops, and hops no longer meant money; and back of all this demoralization and want, stood the poor farmer, the innocent but, nevertheless, suffering victim.

It is a remarkable tribute to the honesty, industry, and thrift of Sauk County farmers of those days to say that within the next ten or fifteen years, the general embarresment consequent upon the failure of this enterprise was almost completely overcome, and exists today, only in the memory of the older portion of the inhabitants of our now rich and prosperous county.