Parades of Reedsburg

A Glorious 4th of July

by Bill Schuette

The first Independence Day celebration that occurred in Reedsburg transpired barely a year after the founding of that village. It was 1849, and there were few materials with which residents could demonstrate their patriotic enthusiasm. They had no flag pole, and in fact, they lacked even a flag. What to do? Our pioneer forefathers being the industrious and innovative lot that they were weren’t going to let the jubilee of their glorious liberty pass by uncelebrated.

Their story is chronicled in The American Sketch Book, History of Reedsburg - 1875.

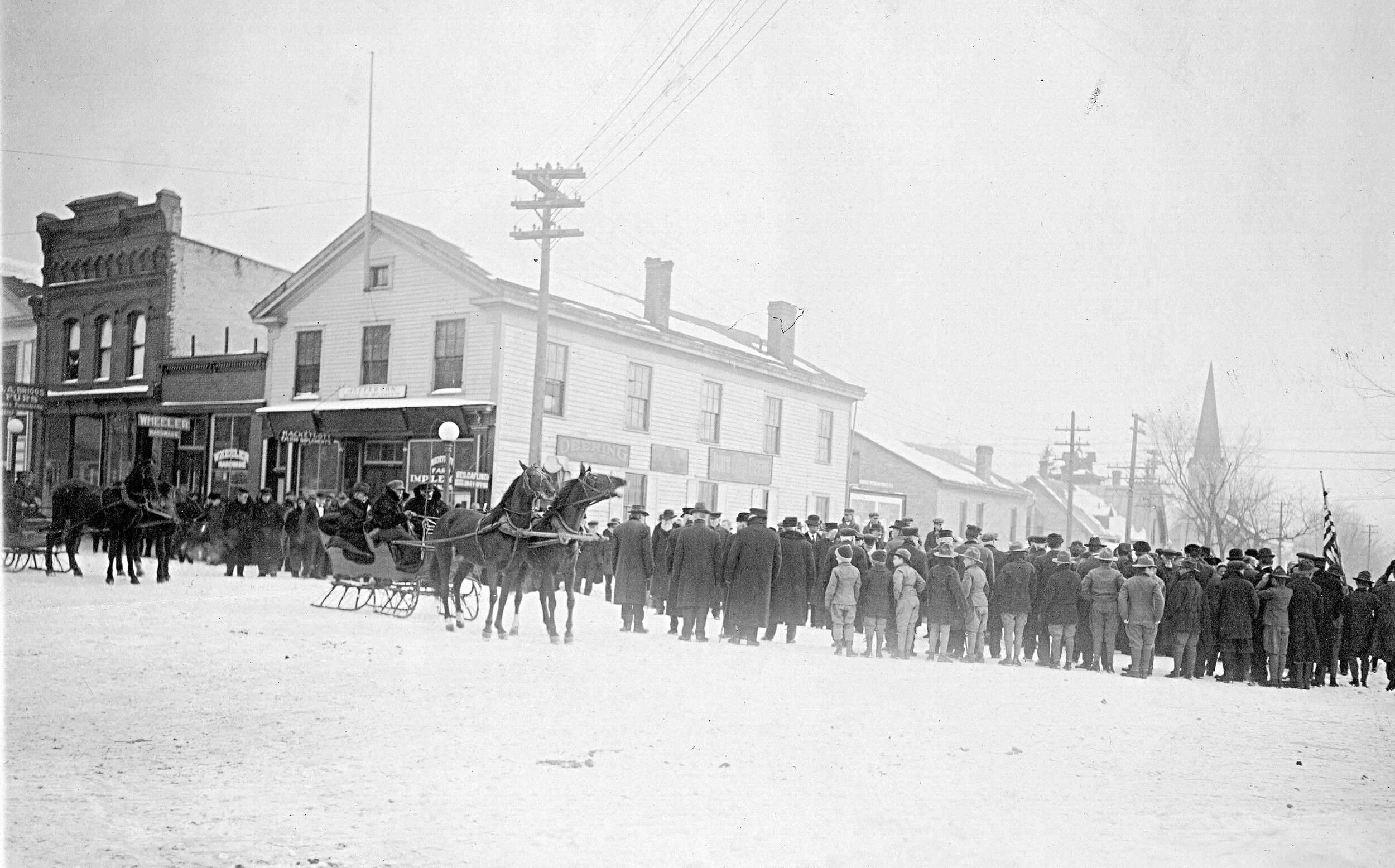

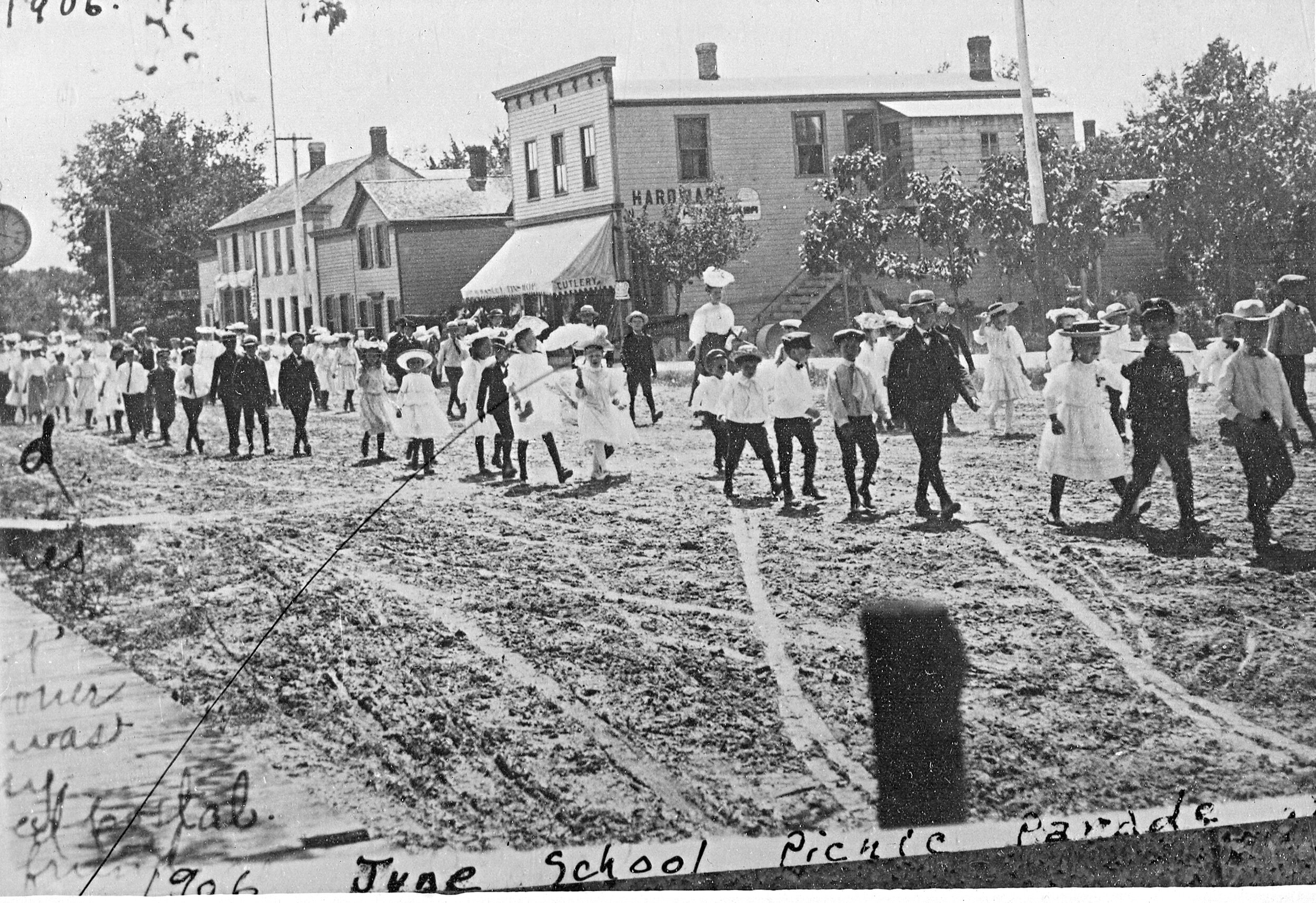

Loganville 4th of July Parade late 1890s

As the men commenced to locate and raise a "liberty pole” from which to fly the stars and stripes, the women went about trying to locate enough cloth from which a flag could be constructed. Since most of the men wore blue denims, it was a possible source of raw materials. However, after much wear, the denims lacked the color with which they were originally endowed. Buckskin patches were commonly sewn to the seats and knees of the pantaloons as reinforcements.

Seamstresses cut out the unfaded denim beneath these patches, and stars were formed from the bright blue fragments of cloth. The white stripes as well as a backing for the flag were made from the women’s undergarments. That left the red stripes. These were cut from the tails of the men’s shirts, shortening them a bit in the process.

All the ingredients were present and the sewing began. But soon the women ran into a problem, they did not know how to make a five pointed star. So instead, all the stars on the flag had six points. "That won’t do," said Horace Croswell after viewing the completed flag. Horace, as the story continues, "Was the ladies’ man at that period, and general confidant. To him the women confided the secret, showing him the flag." He insisted that, "The national star has only five points.” So the six pointed stars were removed, one point cut off and the remainder twisted into the proper shape. A young lady, Agnes McClung, embroidered the following couplet which was attached to the flag: "The star spangled banner, long may it wave, o’er the land of the free, and the home of the brave."

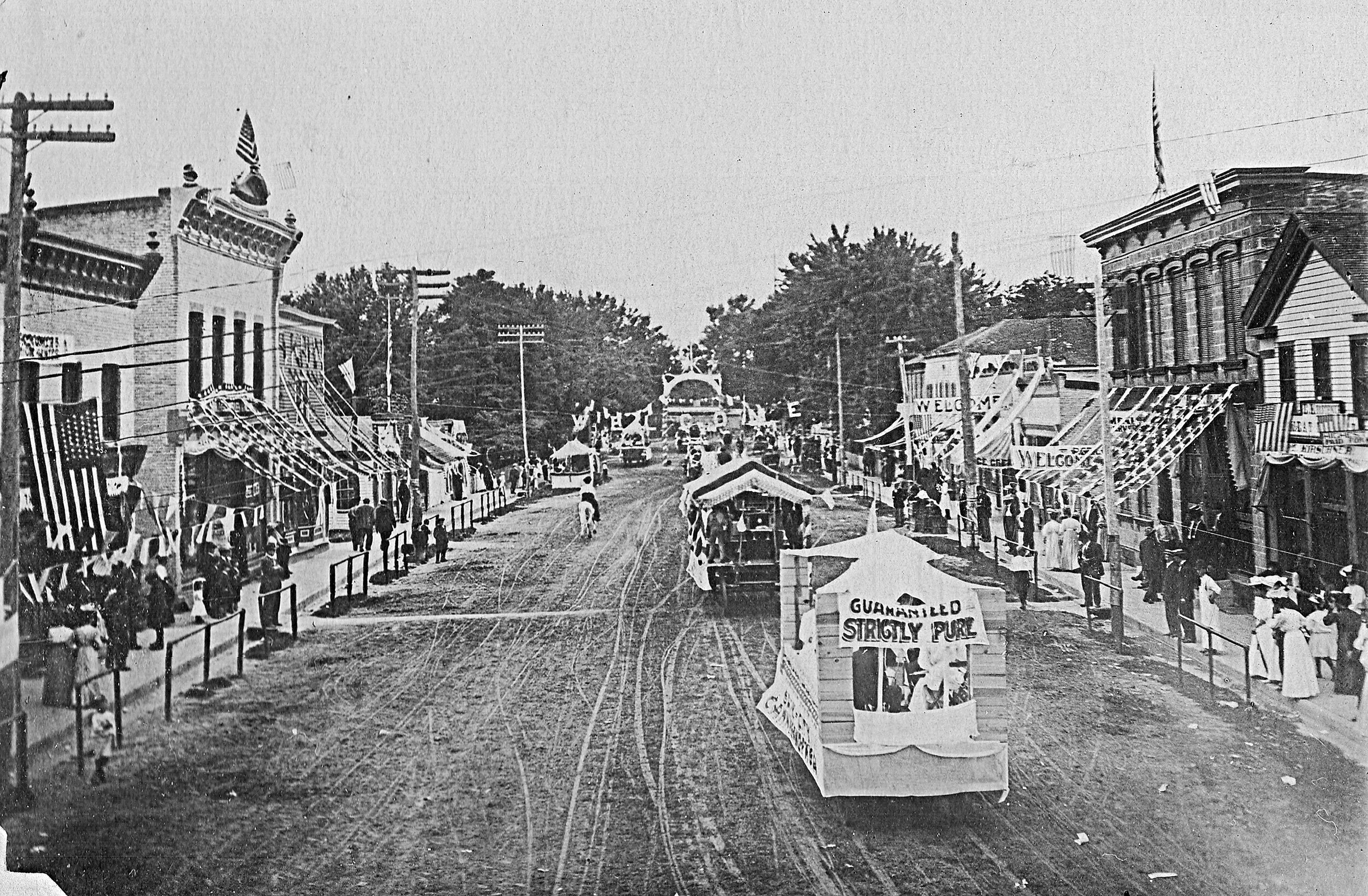

Lodge Float in Lime Ridge

It was customary for all to gather at a sumptuous repast to help celebrate the great day. But, since groceries were few and no one family had all the ingredients to make so much as a pie, all chipped together and a presentable dinner was arranged. In fact, it was more than presentable. The writer noted that, "The dinner, the like of which had never been tasted in this part of the world before, was highly enjoyed, and the remains of it were given to the Indians, that they might make merry too."

Rev. A. Locke gave the address for the day, however he could not remember the date of the signing of the Declaration of Independence, but his listeners bade him "proceed and never mind it."

The celebration commenced in the new mill, which at that time did not have benefit of a roof or floor. A few boards were placed upon the ground and the first dance ever held in the village of Reedsburg lasted well into the night. Celebrants promenaded into the wee hours by the light of flickering tallow candles.

Baraboo pioneers also celebrated the birth of our nation, but in a unique and dangerous fashion. An article by R.T. Warner in 1910, describes the tradition:

“In those days [ca. 1852] we always had a big bonfire on the public square in the evening. But they did have a novel sort of fireworks in those days, the throwing of fire balls. They procured a large number of balls of candle wick which were soaked in turpentine and lighted and then all the boys and some of the men vied with one another in seeing how far and how high these blazing balls could be thrown,” wrote Warner. “It took an expert to pick up a ball and throw it quick enough, to avoid being burned and blistered by the blazing fire balls.

“At one time I remember the courthouse was set on fire, one of the burning balls having lodged on the roof, setting fire to the shingles. But the destruction of the new courthouse, it was new then, was happily averted. Someone, I think it was Frank Graham, having procured a ladder, carried up a bucket of water and extinguished the flames.”

Native Americans were also eager participants in 4th of July celebrations in Sauk County, noted Warner. “There was one feature of these fourth of July celebrations of the early times that always interested the juvenile element which was the shooting of pennies by the young Indians from the Indian camps, who generally visited Baraboo on the Fourth. These were the kids of the Winnebago [now the Ho Chunk] tribe, from 5 to 15 years old, who were usually on hand with bows and arrows to shoot the old fashioned copper cent.” A penny was placed atop a stick set in the ground with a slit cut in it to hold the coin. Participants were lined up behind the stake at a distance of ten paces, and required to “toe the mark!” At a signal from one of the adults, they commenced shooting.

Warner continues, “As soon as one of them got a penny he put it in his mouth and it did not take long for some of them to get a mouth full of pennies. This sport was continued as long as the stock of pennies held out.”

Parades of Baraboo

A Pioneer 4th

by Bill Schuette

Since the first revolutionaries signed the Declaration of Independence in 1776, the 4th of July has been celebrated as a milestone for the freedom of all Americans. Early Sauk County pioneers were no exception, and they marked the day of Independence with celebrations, dances and games.

In a speech to Sauk County Historical Society members, R.T. Warner, an early settler, recounted his experiences during some memorable 19th century 4th of July celebrations in Baraboo:

“...In those days we always had a big bonfire on the public square in the evening. But they did have a novel sort of fireworks in those days, vis: the throwing of fireballs.”

In preparation, celebrants wadded up balls of waxed candle wicks, soaked them in turpentine and ignited them.

“All of the boys,” continued Warner, “and some of the men vied with one another in seeing how far and how high these blazing balls could be thrown. Many hands were burned [as] it took an expert to pick up a ball and throw it quick enough to avoid being burned and blistered by the blazing balls.”

Warner also recalled that on one such occasion, an errant fireball was lobbed onto the roof of the courthouse igniting the wooden shingles. An on-looker quickly located a ladder and doused the fire with a bucket of water.

Another interesting activity which was eagerly awaited by the “juvenile element” of Baraboo, noted Warner, was the shooting of pennies by young Indians from nearby encampments.

“These were the kids of the Winnebago tribe, from 5 to 15 years old, who were usually on hand with bows and arrows, to shoot the old-fashioned copper cent.”

A stake was placed in the ground with a slot on the top into which was placed a penny. The shooters were set ten paces back from the stake, and upon a signal, commenced shooting.

“As soon as one of them got a penny, he put it into his mouth, and it did not take long for some of them to get a mouthful of pennies.”

The 4th was also a glorious occasion for celebration in the little village of Loganville.

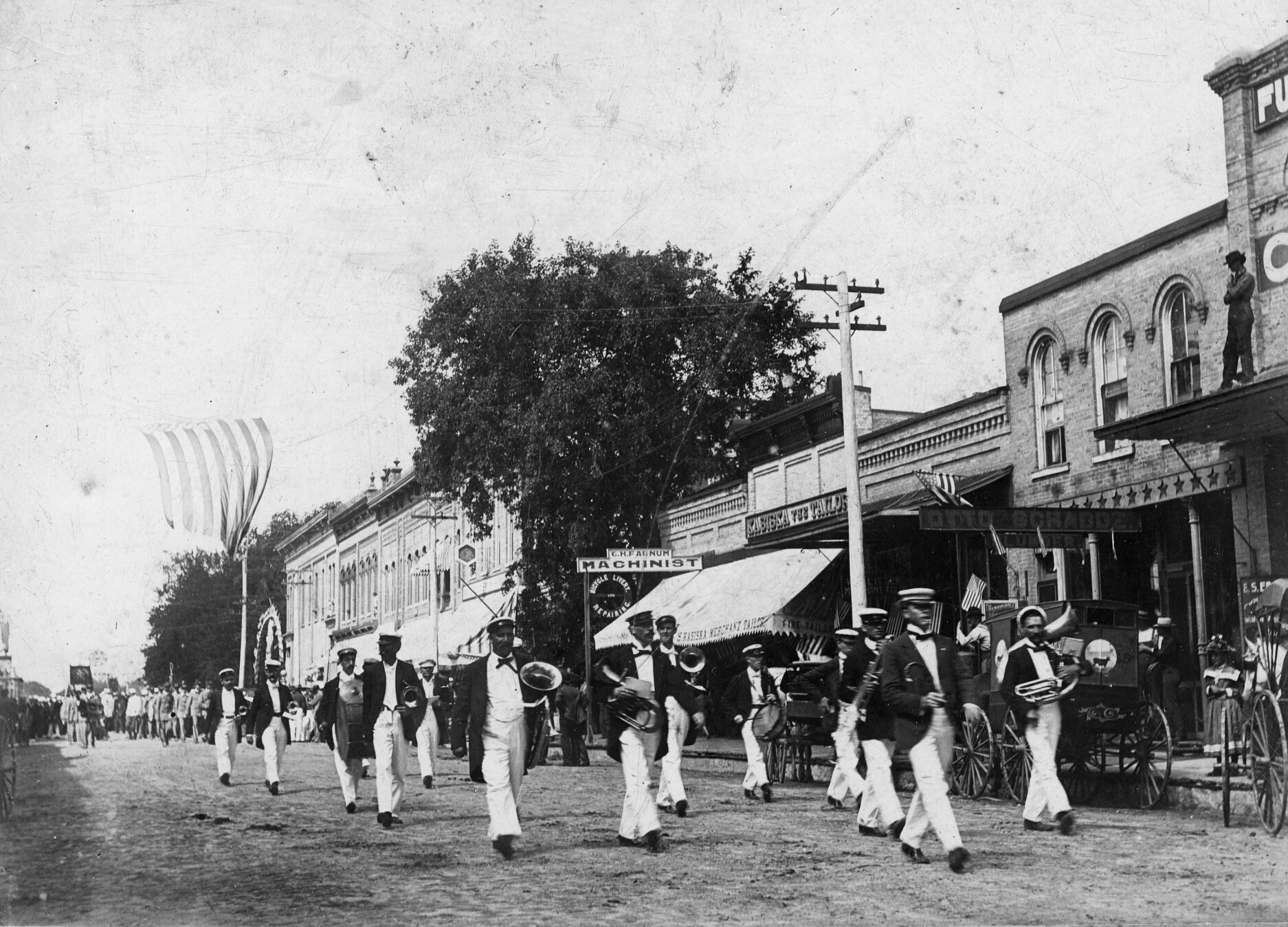

“The day was ushered in by booming of cannons, ringing of bells and the blowing of steam whistles,” noted an 1896 news article. A parade was formed, headed up by local officials and the Reedsburg Drum Corps. “The enthusiasm, like the procession seemed to have no limit. No one could tell how long the procession was, for no one could see both ends of it at the same time.”

Among those proceeding down main street were the “Goddess of Liberty on a spirited steed, 45 girls gaily dressed carrying banners to represent the States of the Union.” Next came young boys “...uniformed in sashes and military hats.” An entourage of the “regular rank and file” followed the parade to a “lavishly decorated speaker’s stand.” Children partook of free lemonade and other goodies. Those assembled concluded the day of celebration with a dance and fireworks.

The first 4th of July celebrated in Reedsburg took place barely a year after the tiny village was settled in 1848. The early pioneers had little with which to construct a national flag, so using their ingenuity, they set about creating the symbol of their independence. Men’s trousers were the right blue color, but wear and washing had taken its toll, resulting in a much-faded color. However, to reinforce the seats and knees of their trousers, buckskin patches were often sewn on. Beneath these patches the bright denim color had survived and the ladies commenced to remove same.

For the white stripes, women’s under garments were pressed into service.

Men’s red shirts were the right color for more stripes, so shirttails were sacrificed for the greater cause. That first rag-tag flag was proudly hoisted up the Liberty Pole for all to see.

A day of feasting and speeches was capped with a dance in the mill, which had yet to receive its roof and floor. Loose planks were assembled and revilers danced into the night by the light of flickering tallow candles.

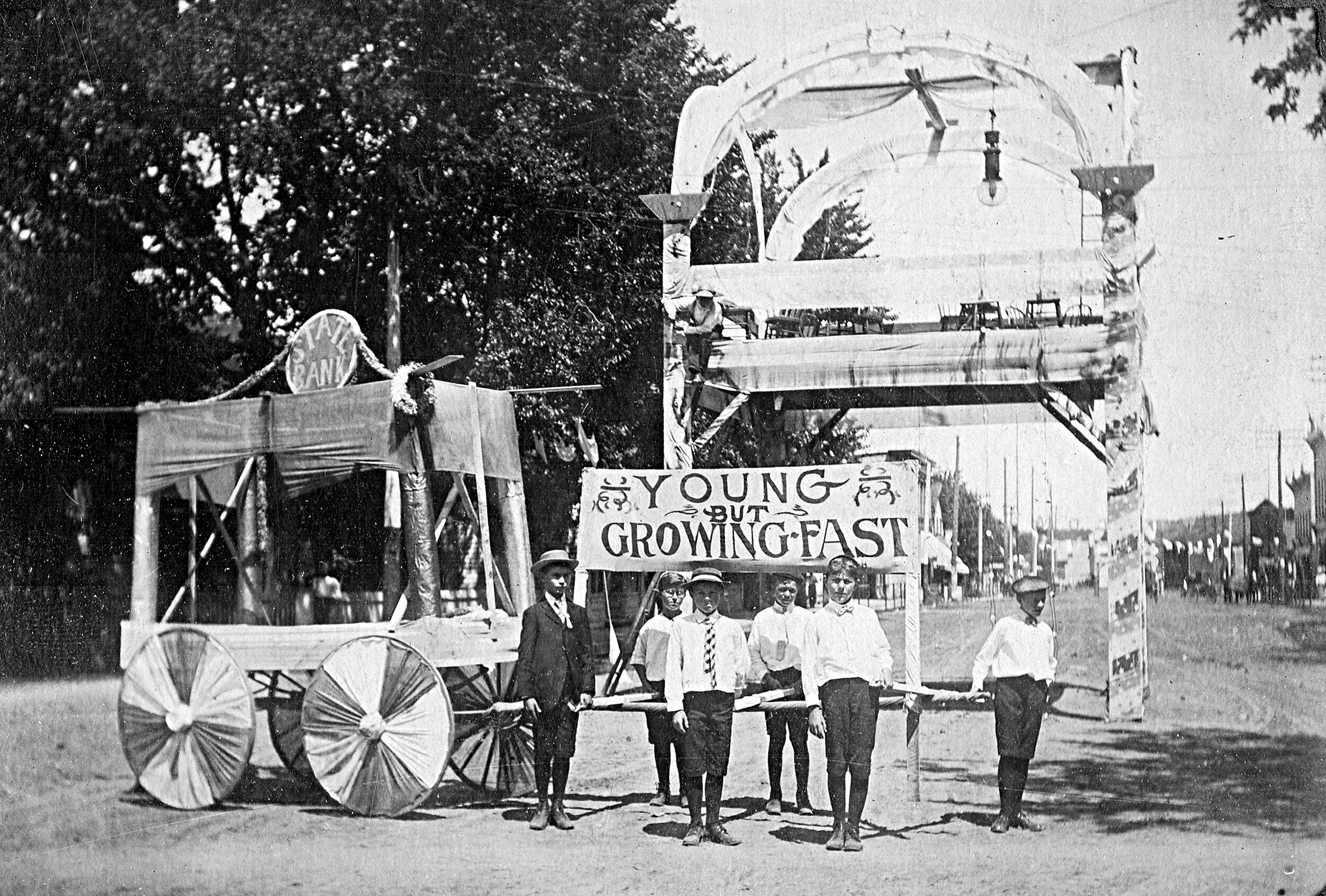

Photo caption: A 4th of July parade wagon in Loganville during the late 1890s.